Paddington to Birkenhead

INTRODUCTION

I have been asked by Harry Corbett to compare the passenger train times between London Paddington and Birkenhead Woodside over a period of years. This Great Western Railway (GWR) route is perhaps little known, Birkenhead being an outpost of GWR services and firmly in London and North Western Railway (LNWR) territory.

This is not an exhaustive review, I have carried it out by reference to timetables and relevant books in my collection (please see credits at the end). I have chosen three specific eras;1920s, 1950s and 1960s from which to analyse specific timetables. The choice of these three eras is not random. The 1920s show a “base line”, a period when the GWR was improving its locomotives and rolling stock. In the 1950s the GWR was of course British Railways, Western Region (BR(WR)), and there was proposed some acceleration of services (see below). The 1960s heralded the arrival of the Western Region diesel hydraulics, the Western Class (or ‘1000s as they were often referred). This article will assess whether the use of these 2,700bhp diesels went further to improve timing. Other comments are extracted from reference works and do cover other periods for reference.

THE ROUTE

Let us start with the route itself. If we trace the 200-mile route from Paddington to Birkenhead, we can then delve into the history of the route and the various railway companies that built and comprised the route. As you will see the route was not planned from Paddington to Birkenhead (unlike Paddington to Bristol, for example) but gradually evolved from improvements to an hotchpotch of existing lines. The description below uses the railways present at/around ”The Grouping” (see below).

Let us start at Paddington.

Paddington to Old Oak Common (OOC) is the original GWR main line and at OOC West Junction the branch is taken to Greenford (GWR). Note that this line by-passes Reading and Oxford so is a more direct route to Birmingham. The section between OOC and Greenford has now been run down and little used over the most recent years (1970s onwards) and the lower section from OOC has now been closed in consequence of the construction of HS2.

At Northolt Junction, the former Great Central Railway (GCR), now the Chiltern line, joins from Marylebone and the route then continued as a joint line through Beaconsfield, High Wycombe, Princes Risborough to Ashendon Junctions, where the former GCR route diverged northwards towards Woodford. In order to maintain speeds and efficiencies the junctions at Ashendon and Aynho are “flying junctions”. Our route remains GWR through Banbury, Leamington Spa, Hatton, Birmingham Snow Hill, Wolverhampton Low Level to Wellington (Salop). From Market Drayton Junction, just west of Wellington to Shrewsbury the line was joint with the LNWR.

At Shrewsbury, and back on GWR metals, the route heads north westerly towards Gobowen and then north to Wrexham and on to Saltney Junction where the GWR tracks joined the Chester and Holyhead route (LNWR). At Chester trains either had to use the avoiding line to join the LNWR/GWR joint route to traverse the Wirral on to Birkenhead or go in to Chester station and run around to depart for Birkenhead, not an ideal situation. Birkenhead Woodside, the terminus, was opened on 31 March 1878 (prior to this trains terminated at another Birkenhead station) and closed on 5 November 1967, the last through services from Paddington running on Saturday 4 March 1967. Birkenhead Woodside was a short walk from the ferry which could then take passengers to Liverpool.

In terms of gradient profile, there was a steady climb from OOC to Seer Green (20 miles), the steepest at 1 in 175 (Denham), after a brief down hill stretch the climb to Saunderton (31 miles) commenced after High Wycombe with two stretches of 1 in 164. This was followed by largely down hill stretches until the climb up Bicester bank commenced (52 miles), largely at circa 1 in 200 for 6-7 miles. This was followed by a 1 in 200 down for 3 miles to Aynho and Kings Sutton (64 miles), then a steady climb up towards Fenny Compton before a long descent of circa 13 miles towards Warwick (89 miles). Then came Hatton bank 4 miles largely at 1 in 103-108. Beyond Lapworth (98 miles) the line had no severe or long gradients until just beyond Soho and Winson Green (112 miles) when a two mile climb up to the Hawthorns at 1 in 100 commenced. The next 35 miles to Upton Magna was largely down hill with a four-mile 1 in 150 up from Gosford to Hollingswood. From Shrewsbury (153 miles) there were a series of up hill followed by down hill sections with summits near Chirk and Ruabon (178 miles). From there is was largely downhill all the way to Saltney Junction and short climbs for the final two miles to Chester (195 miles). Gresford bank offered the most respite for down trains as the descent was 1 in 821/2 for four miles.

HISTORY

Next I think it is appropriate to cover a brief history of the route. As seen above, the Paddington to Birkenhead route was not “pure” GWR all the way as built, but it was an amalgam of, initially, smaller companies that constructed the relevant lines which were absorbed by the GWR and LNWR up until “The Grouping” (that is when the GWR, LNWR, London and North Eastern Railway and Southern Railway emerged as a consequence of the 1921 Railways Act).

If we begin at London Paddington we can of course start with the GWR being founded in 1833 (the enabling Act being 31 August 1835) and which, under Brunel’s influence and guidance, built the Paddington to Bristol line, the first trains running part of the route in 1838.

The GWR built part of the route from OOC West Junction to Ashendon (historically known as the New North Main Line) between 1903 and 1905. Construction of the 7-mile section between OOC and Northolt commenced in early 1901. By 1904 it had been opened as far as Greenford. The section between Northolt Junction and Ashendon, a distance of 333/4 miles, was built as a joint effort with the GCR, opened in November 1904 for goods traffic and remained a GWR/GCR joint line until 1948. The Bill for the GWR Ashendon to Aynho section was deposited in 1905. Once built this connected with the Oxford and Rugby Railway (which was only built to Fenny Compton) and then the former Birmingham and Oxford Junction Railway (BOJR) which had been opened on 1 October 1852. The BOJR owed its origin to the Grand Junction Railway as competition for the London and Birmingham Railway (to Euston). In this regard they sought cooperation of the GWR.

However, before matters progressed with the GWR the Grand Junction joined forces with the London and Birmingham Railway so they bowed out of the OBJR project. The GWR acquired the BOJR on 1 January 1847 (by virtue of a clause included in the Act authorising the building of the line).

The Birmingham, Wolverhampton and Dudley Railway (BWDR) opened on 14 November 1854, connecting through the short Wolverhampton Railway to join the Shrewsbury and Birmingham Railway (SBR). The BWDR was acquired by the GWR in August 1848. Curiously it seems the BWDR at first did not actually reach Dudley (later served by a branch) or Wolverhampton (initially)!

The SBR was authorised in 1846. The section between Wolverhampton and Birmingham was to be supported financially by the LNWR, but they were underhanded. The section between Wellington and Shrewsbury was built jointly with the Shropshire Union Railway. The line opened from Shrewsbury to its own Wolverhampton terminus in 1849. The LNWR remained an impossible business partner and with the GWR reaching Wolverhampton in 1854, the SBR aligned itself with the GWR and merged with it in the same year. The section between Wellington and Shrewsbury became a joint line (GWR/LNWR).

Beyond Shrewsbury to Chester, it is the Shrewsbury and Chester Railway (SCR) that takes us northwards. This was formed in 1846 out of two rivals, the Shrewsbury, Oswestry and Chester Junction Railway, authorised in 1845 and the North Wales Mineral Railway, authorised from Chester to Wrexham in 1844 . Despite various battles the GWR took control of the SCR under an Amalgamation Act on 1 September 1854.

At the northern end of the route the final stretch from Chester to Birkenhead started life as the Chester and Birkenhead Railway on 23 September 1840. It was taken over by the Birkenhead Lancashire and Cheshire Junction Railway in 1847, retaining its own name until it was shortened in 1859 to The Birkenhead Railway. On 1 January 1860 it was taken over by the LNWR and the GWR, remaining a joint railway until nationalisation in 1948.

So by circa 1860 the GWR had the ability to run its own trains on its own railway lines from Paddington to Birkenhead. At that early time the route was via Reading and Oxford and then later in 1910 with a little help from the GCR (for one section of the New North Mainline) and the LNWR (two sections) of joint lines. Furthermore the GW trains would also eventually reach both Manchester and Liverpool by virtue of running powers over LNWR lines from Chester.

We do not consider the route from OOC to Reading, Didcot and Oxford to Birmingham, which was the main route before the New North Mainline opened and after part of that route closed in more recent years.

Of course during the period of railway rivalry (arguably up until Nationalisation in 1948), there was competition with respect to passenger services between the GWR and LNWR to Birmingham, Wolverhampton and Chester. The GWR did consider a 13/4 hour run to Birmingham but took no action to make it a reality. Following Nationalisation there was rationalisation of the network and with the work on the upgrade and electrification of lines out of Euston (LNWR/LMS/LMR) in the early 1960s, the route from Paddington had a revival in the sense of maintaining a good service at least between London and Birmingham. Indeed there was a Blue Pullman train service between Snow Hill and Paddington for a few years. In January 1963 all intermediate stations between Banbury and Princes Risborough (other than Bicester) were closed and by September of that year the WR line from Aynho Junction northwards passed to the LMR. Once the LMR electrification out of Euston was completed the route from Paddington was clearly less competitive and so its rundown continued at a pace and it became a secondary route.

TRAIN SERVICES

A summary of the relevant timetables selected for this article is attached at Appendix 1. The services were selected for similar departure times for each year and their journey times compared. Appendix 2 shows the number of trains daily along with total journey times. This covers both up and down trains on weekdays.

1924

Certain down trains (including the 9.10am Paddington departure selected) completed the trip in less than 5 hours. There were 6 down trains per day.

The up trains took over 5 hours. There were 5 up trains daily.

1955

All down and up trains took well over 5 hours (5 hours 15mins down being the fastest and 5 hours 17mins up). There were 6 down and 5 up trains per day.

1965/6

Timings were improved when compared with the 1950s but were slower than the 1920s. The fastest down train was 5 hours 15mins with the corresponding fastest up train taking 5 hours and 5 mins.

There were 6 up and down trains daily.

A broader view

The above comments are based on selected snap shots. More detail has been gleaned from railway publications where more research (including timing of trains) has been undertaken. If I can borrow from OS Nock’s book “Sixty Years of Western Express Running” we can look at some other illustrations.

For example, going back to 1901 a typical Paddington to Birmingham service via Reading and Oxford (a distance of 129.3 miles) took 143 minutes (4-2-2 No.3051 Stormy Petrel with 10 vehicles of 230 tons) an average of circa 56mph. No.3373 Atbara covered the distance with a relatively light load of 180 tons a net average speed of 65mph (pages 5 and 9). At this time the services out of Euston reached Birmingham in 2 hours, so the GWR was disadvantaged, hence the reason for opening the New North Mainline from OOC West Junction but the GWR also benefited from the capacity created by taking the Northern-bound trains away from the mainline to Didcot. When Ashendon to Aynho Junction opened (length 18.3 miles) in 1910 the distance saved from the Didcot and Oxford route was 18.7 miles. The route length to Birmingham was then 1101/2 miles (being 21/2 miles shorter than the route from Euston). This enabled 2-hour runs to Birmingham.

There were some fast stretches, especially southbound. 88mph was recorded on Gerrards Cross bank and and average of 82.5mph over the 7.2 miles from Gerrards Cross to Northolt with an early County Class locomotive (page 100). However, the eight miles of the Princes Risborough to High Wycombe section suffered from its original branch status and had heavy gradients and severe curves. Elsewhere the new Birmingham route was to become the scene of some of the most consistently spectacular running in Great Britain. From 1910 until the outbreak of war in 1914 the traffic had scarcely developed, and it was between the war it saw its greatest days, as yet (page 75). It was in this era that the GWR with Churchward in charge of locomotive design that 4-6-0s were becoming more prevalent on expresses (displacing the 4-4-0s/4-2-2s). He also looked to improve coaching stock. Slip coach workings came in on the Northern route which helped to maintain fast times. With steam traction one other variable was “firing” and the use of coal. The build up of the fire-bed prior to a run was crucial. On a journey involving heavy work the coal will be level if not slightly above the bottom level of the firedoor before “right-away” is given. Although developed with Welsh steam coals in mind this means of firing was used with success on the two-hour Birmingham expresses in the inter-war period where most were fired on a mixture of Staffordshire and North Wales coals (page 109).

In 1914 the services to Birmingham were covered in 2 hours (fastest time) for the now 1101/2 miles at an average speed of 55.3 mph. By 1918 the fastest time was 150 minutes at an average of 44.2 mph (page 142). A quite drastic increase in time of 30 minutes. However, full pre-war speed returned on the route in 1921 (as it did with other main routes).

Prior to the Grouping the Cambrian Coast Express conveyed a through coach to Birkenhead which divided at Wolverhampton.

The 4.10pm from Paddington (see Appendix 2 for 1924) was the “Belfast Boat Express” to connect with sailings to Belfast. The 9.05am ex-Birkenhead was the equivalent up service. After Nationalisation the boat services were switched to run via the LMR to Liverpool.

The early period services were in the hands of ‘Saint’ and 'Star' class 4-6-0 engines. Increased loadings meant that something more powerful was needed; enter the 4-6-0 ‘King’ Class from 1928, these worked the route until withdrawn en bloc in September 1962. Also new ‘County’ Class and occasionally ‘Castles’ supplemented ‘Kings’. The ‘Kings’ were able to maintain the schedule, despite the heavier loadings and the 9.10am Paddington to Birkenhead was able to stop at High Wycombe and still maintain the 2 hour timing to Birmingham. The maximum load for a ‘King’ Class locomotive was 500 tons between Paddington and Leamington but only 400 tons on to Birmingham because of Hatton bank. Slip coaches facilitated the faster running to avoid more station stops and there were 19 slip workings between Paddington and Birmingham in 1914. These were suspended during the war but never resumed to the same extent in the 1920s. By the early 1930s non stop runs to Birmingham on the route had all but disappeared. The 6.10pm down service to Birkenhead in this period was the “crack express” and worked by a Stafford Road ‘King’ as far as Wolverhampton. Slip coaches for Bicester and Banbury would give the train a stating load of 500 tons. Allowing for a stop at Leamington this train was timed at 901/4 minutes for the 871/2 miles to Leamington. Considering the gradient profile and the unavoidable speed restrictions at certain points it required excellent performances from the locomotive crews.

Automatic Train Control (ATC) was installed OOC to High Wycombe in 1929, Oxford to Wolverhampton in 1931 and Wolverhampton to Chester in 1938/9. It is not clear when High Wycombe to Aynho Junction was so fitted.

The GWR gave consideration to a non-stop schedule of 13/4 hours from Paddington to Birmingham, but this required preparation of speed curves for the route on both up and down lines. The Railway Gazette in early 1938 published these findings. Despite restrictions at High Wycombe and Leamington it was felt that the target was achievable. War stopped further thoughts of this until the mid-1950s.

OS Nock refers to a Railway Magazine article in July 1940, where Cecil J Allen published a summary of George Antrobus’s logs of runs between Paddington and Leamington (a route he travelled regularly and recorded the train times) behind ‘Kings’. A selection as reproduced in OS Nock’s book is summarised below.

This shows the impressive capacity of the ‘Kings’ on such route, albeit they were some of the better examples from total of 1,412 runs!! Nock summarises some runs timed by Mr AV Goodyear; 23 in all with ‘Kings’ (14), ‘Castles’ (4) and ‘Stars’ (5) in climbing the Princess Risborough incline on up trains from Snow Hill. The average speeds “clocked” were ‘Kings’, 55.5mph, ‘Castles’ 57.7mph and ‘Stars’ 56.2mph. The fastest runs for each class were: ‘King’ 5min 47 sec (load 389 tons), ‘Castle’ 6min 81/2sec (load 364), ‘Star’ 6mins (load 418). For the tons hauled the average time taken by the ‘Stars’ was better than the ‘Kings’! Part of the reason for this was two exceptional runs by ‘Star’ class locos (Nos. 4024 and 4063) but the ‘Kings’ were being operated inside their maximum capacity it seems.

With the advent of the Second World War fast trains were decelerated (a general speed limit of 60mph was imposed across the system). However, the London to Birmingham expresses (all stopping at Banbury) made impressive timings from Banbury northwards. The Kings excelled because of their superior ability to lift heavy trains away from their stops.

Post the Second World War there was an increase on passenger usage on the route, the 9.10am to Birkenhead was supplemented by a relief train at 9.00am.

With the arrival of the “new” ‘Counties’ (the ‘1000’ Class) Nock gave some comparisons on the route north of Wolverhampton to Wellington (pages 277-282). This includes a 1 in 100 climb up Shifnal bank for 2.8 miles. For the 19.6 miles a time of 23 minutes was booked. Two ‘Counties’ (Nos.1025 and 1029) did the route in 22mins 52 secs (average speed 60.5mph) and 22mins 25secs (59.4mph) respectively, compared with 23mins for ‘Saint’ No. 2915 (average speed 58.2mph) and 22mins 30sec for ‘Castle’ No. 5022 (59.7mph). The ‘Counties’ had heavier loads than the ‘Saint’ or ‘Castle’ (460 tons for the ‘Counties’ and 445 and 450 for the ‘Saint’ and ‘Castle’ respectively).

Now turning to the up direction of this section of the route, it required a four-mile climb to Hollingswood tunnel, largely at 1 in 132 and 1 in 120 on the final two miles. The scheduled time for up trains from Wellington to Wolverhampton was 26mins, leaving little or no recovery time. Here two ‘Counties’ (Nos. 1025 and 1029) ran it in 25mins 59sec (445 tons) and 25mins and 22sec (500 tons). ‘Saint’ No.2930 managed 26mins 2secs (415 tons) ‘Castle’ No.5064 managed 25mins 51secs (440 tons).

Venturing now to the Shrewsbury Gobowen section of 18 miles, Nock selects 5 trips in each direction (pages 282-284). ‘Saint’ No. 2926 was the star performer with a 20mins 5sec time at an average speed of 67.3mph (max speed 761/4mph) with 300 tons. No.4061 took 22mins and 45secs, but was checked by signals at Gobowen (average speed 60.9mph, max speed 71mph, tons 305). In the up direction, the runs were more spectacular as there are a series of falling gradients soon after Gobowen. ‘Saint’ No.2930 managed the route in 19 mins 8 secs (despite a signal check) with 300 tons (average speed 69.8mph, maximum 761/2mph). ‘Castle’ No. 5061 took 19mins at an average speed of 71.3mph. The maximum speed was 771/2 mph but was only hauling 275 tons. ‘Hall’ Class No.6941 managed the route in 20mins 40secs an average of 65.8 mph and maximum speed of 711/4 mph but was hauling 465 tons!

Returning to the southern part of the route, OS Nock covers a series of timed runs in the late 1940s between Paddington and Leamington, Banbury and Paddington, and Birmingham and Paddington (pages 181-190) which brings the timings, the exploits of the footplate crew and the nature of the route to life. There is too much to repeat here but it makes an interesting read. However, he did have a comparison between and ‘Castle’ and a ‘King’ both independently working the 6.10pm Paddington to Wolverhampton (pages 221-224). No. 4088 Dartmouth Castle with 440 tons tare (475 tons loaded) and No. 6019 King Henry V with 437 tons tare (475) were recorded. It seems the ‘Castle’ performed better than the ‘King’ to High Wycombe (with rising gradients). However, the ‘King’s’ superior tractive power was in evidence in recovering from slacks at Wycombe and Ashendon Junction. No.6019 sustained 551/2 mph up the 1 in 200 from Bicester to Ardley. There was little to choose between them for time keeping based on net timings.

There was disruption in the mid 1950s: the ‘Kings’ had bogie problems leading to temporary withdrawal for remedial works, rebuilding of Banbury station and remedial work to the viaducts at Souldern. In May 1956 ex-LMS ‘Princess Royal' Pacifics were stood in for the ‘Kings’, along with ‘Castles’. In 1956/57 the 30-year old ‘Kings’ were fitted with double blast pipes, double chimneys and four-row superheaters, giving them a new lease of life.

Nock has a record of a dynamometer car trial on the Birmingham route with double- chimneyed ‘King’ No.6002 King William IV (pages 368 to 370). It was 1956 and the 3pm up from Snow Hill was “a very pale shade of its former self”, with 86 minutes allowed for the 67.5miles from Banbury to Paddington, compared with the pre-war 70 minutes. In fact on this run the ‘King’ made it in 75 mins 18sec despite two pw slacks. Nock commented “the running was just what would be expected from a ‘King’ in pre-war days” and stressed the benefits of the double chimney in reducing the back pressure.

In a final look at steam traction on the route again we borrow from OS Nock referring to a footplate ride of Baron Gerard Vuillet (pages 378 and 379). The train was the down “Cambrian Coast Express” with double-chimneyed ‘Castle’ No.7024 Powis Castle hauling 285 tons (8 coaches). The engine worked through to Shrewsbury with total net running time for the 152.1 miles from Paddington adding up to (only) 1561/2 minutes, which includes the slow section from Snow Hill to Wolverhampton. The fastest speeds were achieved down Albrighton bank (90mph) and Upton Magna (80mph) on the latter section after Wolverhampton.

The Westerns took over on 10 September 1962. Laurence Waters (in his book Paddington to Wolverhampton, page 56) stated the impact of these diesels was immediate. He refers to the trains being rescheduled to cover the 110 miles to Birmingham in 2 hours including various stops. This can be seen by reference to Appendix 1 below (1955 compared with 1966). In August 1963, D1040 ‘Western Queen’ was at the head of the Birmingham Pullman (standing in for the unit, which had failed) and collided with a freight at Knowle and Dorridge, the driver died.

The last through train to Birkenhead ran on 4 March, hauled part of the way by No. 7029 ‘Clun Castle’ (by then in private ownership).

Stafford Road (closed in 1963) and Old Oak Common sheds were the main providers of the steam locomotives for the Birkenhead services throughout the period. In June 1962 Oxley received D1000/2/4/5 in its allocation. However, the new diesels* were initially unreliable and some ‘Kings’ were reinstated to cover for the failures. ‘

SUMMARY and CONCLUSIONS

Overall there is broadly little difference between the years and the services selected. Journey time in 1924 was quicker than in 1955 or 1965/6. What the earlier timings represent is more through trains and less local stops. The main part of the route was clearly Wolverhampton, Birmingham and London. Once beyond Wolverhampton the services took circa 3 hours to travel to and from Birkenhead (some fast trains taking circa 2 hours 30 mins). There was probably capacity to improve timings in the northern section including fewer stops but it strikes me that beyond Shrewsbury the Birkenhead bound trains stopped at a number of the smaller stations to provide a more “local service” a bit like the Paddington expresses to the South West getting to Plymouth and then meandering to Penzance.

The number of trains from Paddington to Birkenhead on weekdays broadly remained the same: 6 down trains (including and overnight train/sleeper), 5 up trains (but with a 6th, the sleeper, running in 1966). Restaurant and buffet capacity was provided, usually to/from Wolverhampton but occasionally to/from Shrewsbury as noted.

So rather than improve the timing on the route from decade to decade it seems the GWR were keen to compete with the LNWR/LMS as far as Birmingham until Nationalisation, at which point following electrification out of Euston the route out of Paddington was “doomed” as an express route and after fulfilling a role during the electrification of the LMR route it was relegated to a secondary route.

References

British Railways Pre-Grouping Atlas and Gazetteer (Ian Allan)

British Railways Atlas 1947 (Ian Allan)

History of the Great Western Railway Volumes 1,2 and 3; Vs 1 & 2, ET MacDermot, revised by CR Clinker, V3, OS Nock (Ian Allan)

Sixty Years of Western Express Running, OS Nock (Ian Allan)

Paddington to the Mersey, Dr R Preston Hendry & R Powell Hendry (OPC)

Paddington to Wolverhampton, Laurence Waters (Ian Allan)

The Great Western Railway (GWR 150), Patrick Whitehouse and David St John Thomas (Greenwich Editions)

GWR/BR(W) Public time tables for the relevant periods

Also with thanks to Google!

*The Westerns went on to become the most successful and most appreciated of the hydraulic locomotives and were a match for any diesel electric of their era.

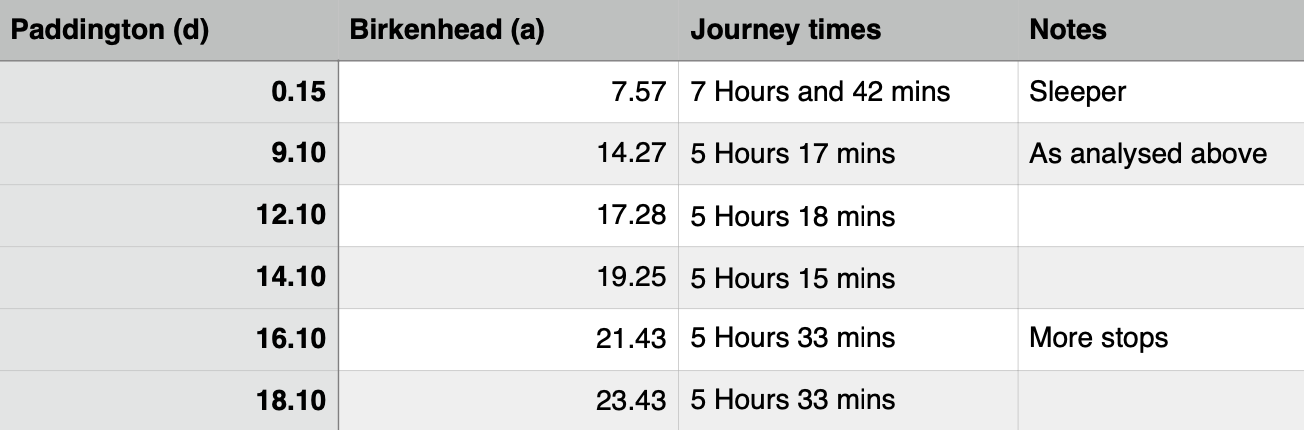

Appendix 1

Weekdays-Summary of down trains for selected periods

NB all times arrival times unless otherwise stated.

In 1924 Banbury and Leamington Spa were served by slip coach. The 9.10 was “badged” in the time table as “Birmingham and North Express” and had through coaches for Pwllheli.

In 1955 The Restaurant car was attached from Paddington to Shrewsbury. The timetable stated Through Coaches Paddington to Stratford upon Avon and Birkenhead.

1965/66 Buffet car off at Wolverhampton. It is presumed the 10 minute stop at Shrewsbury was for a locomotive change.

Weekdays-Summary of up trains for selected periods

Appendix 2

Down trains during the day 14 July to 21 September 1924 (Weekdays)

Down trains during the day 27 June to 18 September 1955 (Weekdays)

Down trains during the day 14 June 1965 to 17 April 1966 (Weekdays)

Restaurant or buffet cars were available on most services from Paddington to Wolverhampton.

Summer Saturdays in this period showed similar services/times.

Sundays showed 4 services (including the sleeper). The three day time services (departing Paddington at 11.10, 14.10 and 16.10 all took over 6-6 hours 30 mins to reach their destination.

Up trains during the day 14 July to 21 September 1924 (weekdays)

On Sundays there was one train departing 2.55pm arriving at 9pm, conveying a tea and dining car.

Up trains during the day 27 June to 18 September 1955 (weekdays)

At this time there appear to be 4 up trains on a Sunday

Up trains during the day 14 June 1965 to 17 April 1966 (weekdays)

Sundays had three through trains plus the sleeper.

Copyright Freddie Huxtable 20 February 2021

Freddie Huxtable

Freddie, by profession, is a Chartered Accountant and Chartered Tax Adviser specialising on high net worth individuals, including Sportspersons and Entertainers. He is a partner at RSM the 7th largest accounting firm in the UK.

Freddie has written a comprehensive history of the Taunton to Barnstaple railway line, a three volume work (published in 2016, 2017 and 2020) covering all aspects of the line from its beginnings to closure and operational matters. He has just commenced work on his next railway project-a book of the railways of the West Country, this will be a book of colour photographs covering the period circa 1955-1975, along with historical references and key facts.